Grayson Perry has been observing certain aspects of British

public; watching what people wear, people’s hobbies, and inspecting

possessions. He has been getting an insight into the personal lives of the

working, middle and upper classes, the details of modern life, and the truths

those details reveal about certain communities. What is behind people’s choices

to buy certain things and live in a particular way? What do individuals think

about themselves? Perry has been on safari through the taste tribes of Britain,

looking at events and rituals that reveal the most about someone’s class and

background, to produce six panoramic tapestries for an exhibition at the

Victoria Miro Gallery, The Vanity of

Small Differences.Beginning his investigation in Sunderland, a city with

strong working class traditions, Perry looks at how early upbringing can have

an effect on later life, and the traditions of the men and women to show they

belong to the ‘tribe’. He notices how the middle and upper classes look down on

the lower classes in a snobbish way, but what taste defines the lower classes?

What is working class taste? Sunderland’s men drive fast cars with subs, have

big tattoos and practice cage fighting as a primitive or even sexual display

whereas the women wear short dresses, big hair, and fake tan; they are their

dream persona at the weekend when they go out as an escape from reality. It is

‘beauty you can measure with a ruler’, there are ‘standards that have to be

met’. Just because someone belongs to a tribe, does that mean they enjoy it or

could they want to escape it? This is another idea behind Grayson Perry’s work,

not only trying to define the taste in the class system but also the feelings

from the classes themselves. The Adoration of the

Cage Fighters is the first of six tapestries produced for this exhibition.

The first words on the tapestry communicate: ‘I could’ve gone to uni’ which is

a poignant statement to illustrate the ticket to a better life that education

can have. The main figure on the right is mirrored to the figure in Adoration of the Shepherds by Mantegna;

all six of the tapestries have references to religious paintings.

The Adoration of the Cage Fighters

Two cage fighters kneel before the main figure offering membership to the working class just as four ladies on the right are trying to persuade the figure to ‘come out for a drink on a Friday night’. The grandmother in the centre will surely stay at home and look after the baby. The baby is symbolic of Tom Rakewell, illustrated in the series of paintings by William Hogarth called A Rake’s Progress. For these tapestries, Grayson Perry has changed the name to Tim Rakewell to modernise the character, which appears in the other six works as a progression, such as the influence of Hogarth; his paintings just as relevant today as when they were created in 1733.

The Adoration of the Shepherds, Andrea Mantegna, 1450

The second tapestry in relevance to the working class taste is called The Agony in the Car Park inspired by a singer Perry met in a night club in Sunderland. The words on the tapestry read: ‘Ship building bound this town together like a religion’, referring to the working class traditional occupations of the area and showing the story of class mobility. On the right of the tapestry, boy racers have ‘Mating Call’ stamped on their cars to symbolise the reasoning behind these young men’s choices and the rituals that ‘get the girls.’ This scene is a lot more emotionally charged and so refers to the emotional structures that form taste. The composition of the piece is associated with two religious paintings; The Agony in the Garden by Giovanni Bellini, and the Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grunewald, which both have a main figure centred in the painting with smaller figures surrounding or gathering round. Furthermore, the viewpoint is mostly similar to The Agony in the Garden as the viewer’s perspective is very high up, showing the surrounding landscape.

The Agony in the Carpark

The Agony in the Garden, Giovanni Bellini, 1465

Isenheim Altarpiece, Matthias Grunewald, 1512-16

The second tapestry in relevance to the working class taste is called The Agony in the Car Park inspired by a singer Perry met in a night club in Sunderland. The words on the tapestry read: ‘Ship building bound this town together like a religion’, referring to the working class traditional occupations of the area and showing the story of class mobility. On the right of the tapestry, boy racers have ‘Mating Call’ stamped on their cars to symbolise the reasoning behind these young men’s choices and the rituals that ‘get the girls.’ This scene is a lot more emotionally charged and so refers to the emotional structures that form taste. The composition of the piece is associated with two religious paintings; The Agony in the Garden by Giovanni Bellini, and the Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grunewald, which both have a main figure centred in the painting with smaller figures surrounding or gathering round. Furthermore, the viewpoint is mostly similar to The Agony in the Garden as the viewer’s perspective is very high up, showing the surrounding landscape.

The Agony in the Carpark

The Agony in the Garden, Giovanni Bellini, 1465

Isenheim Altarpiece, Matthias Grunewald, 1512-16

The working class have been

summarised in these first two tapestries, the cage fighting, the ‘mating call

cars’, the dressed up girls, the lack of education to the working classes, and

their own individual tastes and choices. They answer the question: ‘Who do we

think we are?’

Stereotyping the classes, general views of the public consider the middle classes to have more aspiration than the working classes, opting for branded and more corporate clothing, Land Rovers, dinner parties etc. to subtly give off signals of richness including the cleanliness and perfection of houses. As Grayson Perry considers himself to be middle class, he wonders, is there an upper middle class and a lower middle class? Are the middle classes separated into tribes? Does the more money you have mean the more choices you can make which ultimately mean better taste? But what is better taste? The middle class are considered self- made people, but also people who are not certain of their place in society, being somewhere in between. This lost identity of the middle classes causes angst and agony in looking effortless, feeling a sense of not belonging and therefore wanting to belong.

Expulsion from Number 8 Eden Close is the third tapestry in the series, showing snippets of taste in the middle classes. The two figures in the middle represent Tim Rakewell and his girlfriend (in referral to Tom Rakewell in Hogarth’s A Rate’s Progress) and mirror Adam and Eve in another religious painting Adam and Eve Expelled from Paradise, painted by Masaccio in 1424-25. The split between the two scenes illustrates the lack of belonging in the middle classes; tiny details from Grayson Perry’s research in Tunbridge Wells are noticed also, the William Morris wallpaper, the Land Rover, the golf, the homemade cupcakes and the obsessive cleaning rituals of ‘perfect housewives.’ The chalice in the painting symbolises the middle classes and can be seen in the twinned middle class piece, The Annunciation of the Virgin Deal.

Stereotyping the classes, general views of the public consider the middle classes to have more aspiration than the working classes, opting for branded and more corporate clothing, Land Rovers, dinner parties etc. to subtly give off signals of richness including the cleanliness and perfection of houses. As Grayson Perry considers himself to be middle class, he wonders, is there an upper middle class and a lower middle class? Are the middle classes separated into tribes? Does the more money you have mean the more choices you can make which ultimately mean better taste? But what is better taste? The middle class are considered self- made people, but also people who are not certain of their place in society, being somewhere in between. This lost identity of the middle classes causes angst and agony in looking effortless, feeling a sense of not belonging and therefore wanting to belong.

Expulsion from Number 8 Eden Close is the third tapestry in the series, showing snippets of taste in the middle classes. The two figures in the middle represent Tim Rakewell and his girlfriend (in referral to Tom Rakewell in Hogarth’s A Rate’s Progress) and mirror Adam and Eve in another religious painting Adam and Eve Expelled from Paradise, painted by Masaccio in 1424-25. The split between the two scenes illustrates the lack of belonging in the middle classes; tiny details from Grayson Perry’s research in Tunbridge Wells are noticed also, the William Morris wallpaper, the Land Rover, the golf, the homemade cupcakes and the obsessive cleaning rituals of ‘perfect housewives.’ The chalice in the painting symbolises the middle classes and can be seen in the twinned middle class piece, The Annunciation of the Virgin Deal.

Expulsion from Number 8 Eden Close

Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, Masaccio, 1424-25

The possessions and still life of the middle classes is emphasised

in The Annunciation of the Virgin Deal,

with a Cath Kidston handbag, Penguin book mugs, iPads, car keys and Union Jack

printed cushions. The narrative shows Tim Rakewell’s business partner (portrayed

as an angel) coming to share the news that he has successfully sold his company

to virgin for £270 million pounds, which can be seen in an article on the

screen of the iPad. Tim Rakewell sits comfortably on his sofa with his child in

his arms and his wife in the kitchen, enjoying his wealth. The coffee jug in

the centre is the central icon of the middle classes, just as the chalice was a reference in the previous tapestry. The middle classes are most aware of what they buy, why they buy it and the effect it will have on them and how they are portrayed by others around them. They are self- conscious of the whole taste phenomenon, and there is competition in who can be the most individual.

The Annunciation of the Virgin Deal

The Annunciation, Giotto Di Bondone, 1305

In search of the traditional upper class taste, Perry visits the Cotswolds, filled with mansions and stately homes, where people are stuck in their aristocratic ways, describing themselves as good quality, understated, appropriate and flawless, ‘the posher the person, the less they have to prove.’ There is a spell that is cast over everyone by the upper class, the intimidation felt and the ‘perfection’ that seems to radiate from them. Clothing is deemed more a uniform than a way to express personality, the upper classes have a stronger family tree and so the upkeep of a family’s reputation than be more important than finding one’s own person. Ancestors portraits hang in hallways, clothes are handed down through generations from mothers, grandmothers and great grandmothers, still worn today; very English and very historical. But when faced with the pressure of carrying on tradition, whether this may be inheriting property or taking over a family business, does this make it harder to develop a personal taste? Does upper class taste mean not having any taste at all and just carrying on with what has always been done?

Lord Bath, or Alexander Thynn, the 7th marquess of Bath and owner of Longleat House in Somerset, broke out of these traditions, and transformed one wing of the house into a blank space where he could redesign and paint anything and anywhere he wanted, filling it quickly with his own art, very much with a Bohemian taste. He commented: ‘My space, my canvas.’ which is a powerful statement to show the contrast with the lack of change in upper classes. They are an endangered tribe; they are fighting for survival in an age where the modern world is slowly destroying a traditionalist culture.

In search of the traditional upper class taste, Perry visits the Cotswolds, filled with mansions and stately homes, where people are stuck in their aristocratic ways, describing themselves as good quality, understated, appropriate and flawless, ‘the posher the person, the less they have to prove.’ There is a spell that is cast over everyone by the upper class, the intimidation felt and the ‘perfection’ that seems to radiate from them. Clothing is deemed more a uniform than a way to express personality, the upper classes have a stronger family tree and so the upkeep of a family’s reputation than be more important than finding one’s own person. Ancestors portraits hang in hallways, clothes are handed down through generations from mothers, grandmothers and great grandmothers, still worn today; very English and very historical. But when faced with the pressure of carrying on tradition, whether this may be inheriting property or taking over a family business, does this make it harder to develop a personal taste? Does upper class taste mean not having any taste at all and just carrying on with what has always been done?

Lord Bath, or Alexander Thynn, the 7th marquess of Bath and owner of Longleat House in Somerset, broke out of these traditions, and transformed one wing of the house into a blank space where he could redesign and paint anything and anywhere he wanted, filling it quickly with his own art, very much with a Bohemian taste. He commented: ‘My space, my canvas.’ which is a powerful statement to show the contrast with the lack of change in upper classes. They are an endangered tribe; they are fighting for survival in an age where the modern world is slowly destroying a traditionalist culture.

The Upper Class at Bay

This can be depicted in The

Upper Class at Bay, the fifth tapestry to define the third type of class,

showing the ideas and tastes coming to a dead end. The upper class is portrayed

as prey or an endangered species brought down- ‘The Hunter and the Hunted.’ Tim

Rakewell is viewed on the right with his wife, witnessing the killing of a

tatty, tweedy old stag. The stag represents a dying patriarch who has run his

course and is being mauled by the ‘dogs of tax’. The distortion which can be seen in not just this tapestry, but

all six, gives a nightmarish quality and a hazy sense of reality. The stag is

being watched with satisfaction that the old is being undermined by the new.

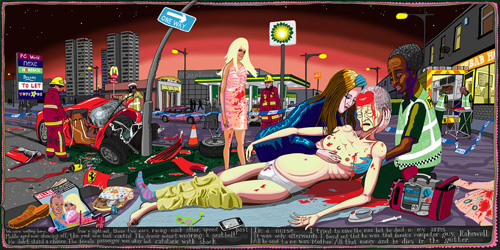

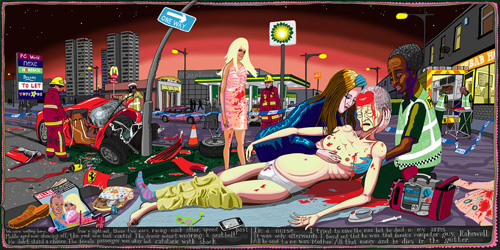

#Lamentation

#Lamentation

The Lamentation, Rogier Van Der Velden, 1441

#Lamentation is the final scene that completes the series, in which Tim Rakewell has brought himself a new car and in flaunting this to his new wife, races down the street, only to end up crunched into a lamp post, flying through the windscreen and ending dying in the gutter in a tragic turn of events. Accessories scattered around him illustrate the celebrity lifestyle, being featured in the latest ‘Hello’ magazine, his iPhone smashed up, his blonde bombshell wife standing distraught in the road. The hash tag at the beginning of the title refers to the audience of people in the scene, tweeting pictures and status updates of the celebrity crash, oblivious to the feelings of dying Tim Rakewell. The composition mirrors A Lamentation by Rogier Van Der Velden, the religious undertones contrast with the false, money-grabbing life of Tim Rakewell in his success through the classes to the top.

#Lamentation is the final scene that completes the series, in which Tim Rakewell has brought himself a new car and in flaunting this to his new wife, races down the street, only to end up crunched into a lamp post, flying through the windscreen and ending dying in the gutter in a tragic turn of events. Accessories scattered around him illustrate the celebrity lifestyle, being featured in the latest ‘Hello’ magazine, his iPhone smashed up, his blonde bombshell wife standing distraught in the road. The hash tag at the beginning of the title refers to the audience of people in the scene, tweeting pictures and status updates of the celebrity crash, oblivious to the feelings of dying Tim Rakewell. The composition mirrors A Lamentation by Rogier Van Der Velden, the religious undertones contrast with the false, money-grabbing life of Tim Rakewell in his success through the classes to the top.

No comments:

Post a Comment